When Hungarian-Jewish architect László Tóth (Adrian Brody) emerges from the bowels of a refugee boat fleeing the fallout of World War II, we discover America the instant he does. Lady Liberty heralds him, illuminating with her torch the whole of the American landscape. He is free—or is he?

The stark image of the Statue of Liberty is upturned against a white sky by director Brady Corbet in a frame with no discernible horizon line. Uncut for nearly a full minute, the image begins to evoke a warning more than a beckoning. Perverse as an inverted American flag, it is a signal of distress.

Throughout “The Brutalist,” freedom is a key theme questioned but never answered. For Tóth, freedom transmutes from eluding fascism into creative liberty—but that’s before it’s revealed as only a chimera.

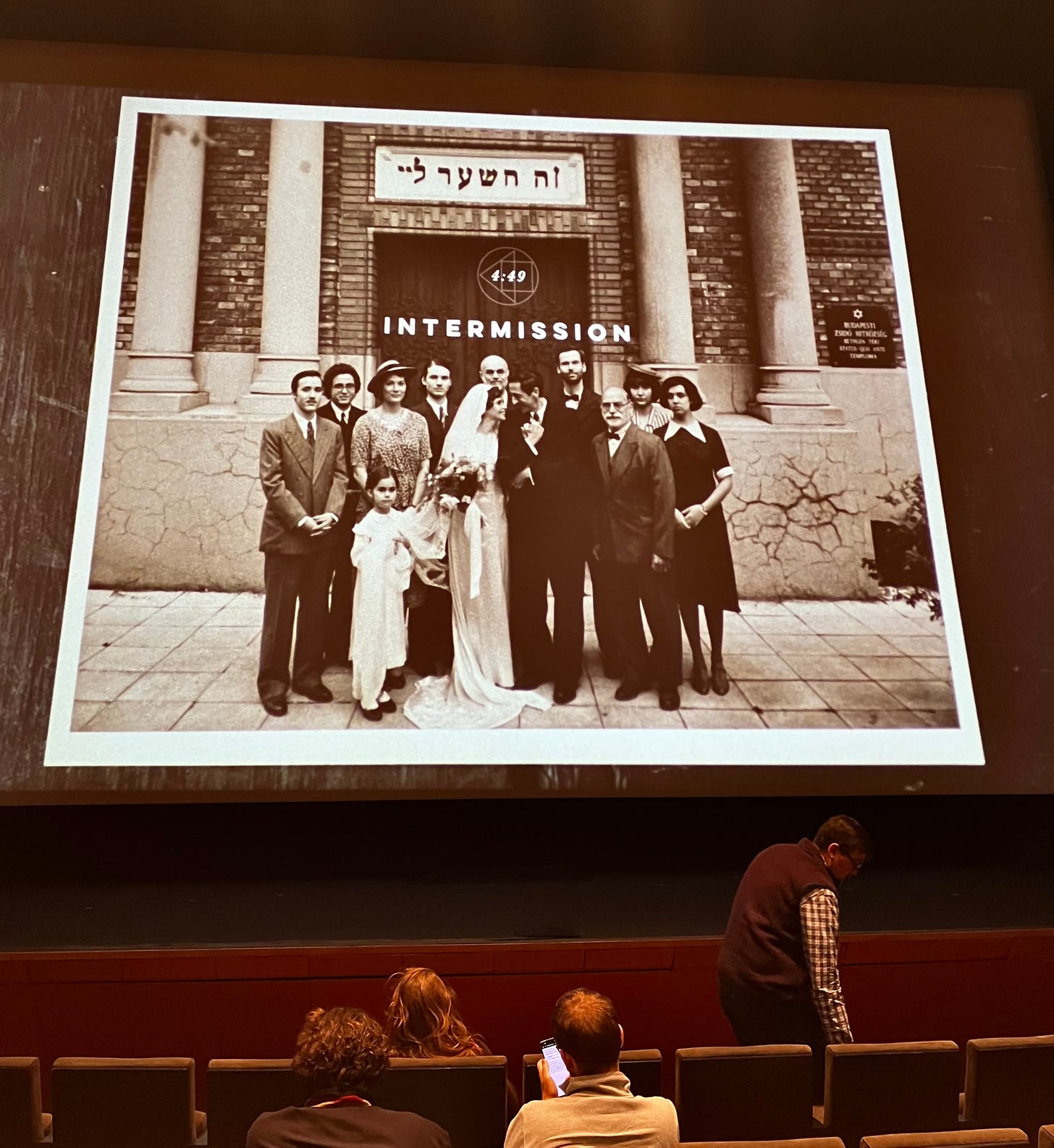

For the nearly four-hour runtime (which includes a 15-minute intermission burned into the film’s reel complete with a countdown clock), Tóth invests in sovereignty always pulled out from under him. In the front half of the film, he finds refuge in a backroom of Miller & Sons Furniture, a showroom owned by his cousin Attila in Philadelphia. Attila (Alessandro Nivola) has Americanized his surname and contrasts Tóth’s broad trousers and jackets with tailored three-piece suits. The furnishings on display reflect a post-war America predicated on conservative functionality. When Tóth fashions an experimental seating-storage hybrid reflective of his Bauhaus training, it’s likened to a tricycle.

Redemption seems to abound when the strapping but stuffy Harry Lee Van Buren (Joe Alwyn), taps the Tóths to transform his father’s private reading room as a surprise. At the stately Van Buren manor, Tóth guides the overhaul of the dense and imposing space from something akin to the Red Room in “Twin Peaks” into a sanctuary. Heavy curtains and dark surfaces are stripped away and replaced with wooden fins that conceal bookshelves, simplify the palette, and concentrate the generous light of its windowall. Amidst an altogether altered geometry, the centerpiece is a single brutalist lounger sunbathing at its core.

Though my audience gasped at the room’s reveal, Harrison Lee Van Buren (a venomous Guy Pearce) erupts at the takeover. Thoroughly debased by his cousin and client, Tóth relinquishes himself to day labor before the Van Burens seek him out again with contrition. “You were not prepared for what you saw. That is understandable,” Tóth offers. “I’m glad you’ve come to appreciate it.”

After being wined and dined among the Old Money of Greater Philadelphia society, our hero is theatrically enlisted to spearhead the design of a sprawling, interfaith community center in honor of the Van Buren matriarch. Van Buren’s generosity extends further when he promises to machinate the liberation of the surviving Tóths out of Europe and into America with the caveat that both families coexist at the bucolic Van Buren compound.

The clean lines of the complex Tóth drafts are compared to a barracks, even with a materiality anchored in softly veined marble. Tóth’s vision of a linear succession of small rooms, high ceilings, and a below-grade passage unifying all four volumes is met with suspicion from developers whose biases go deeper than budgets. The concept begins to resemble a monument, an embodied legacy complete with an altar to heap worship upon.

“… his buildings inspire and uplift. They invoke the freedom he pursued before he built it himself.”

The message here isn’t subtle: American exceptionalism desecrates the purity and genius of the outsiders who touch it. The monuments raised to commemorate its might are fated to become tombs one day toppled. And those like Tóth, who are patronized by hubris masked as good intention, are humiliated until forced compromise and cruelty birth something hollow and cold.

Beyond the verdurous hills of rural Pennsylvania, the film includes jaunts up to Manhattan and even a breathtaking journey among the stones of Carerra, where the metaphor takes a grave—and literal—turn. Corbet’s signature menace pervades the film’s second half, in which the audience is smeared into hazy sequences where pain is love, love is only sex, and sex is violence.

What grows steadily from the background to the foreground of the narrative is the establishment of the Israeli state. Disputes about abandoning America in favor of yet another new beginning are volleyed between Tóth and his family, who are nauseated by American ignorance and extravagance the instant they arrive. It’s cathartic when Tóth’s wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) finally spews her distaste (“This country is rotted.”) in the film’s final stretch, but her pursuit of purity in the form of aliyah already feels tainted. The argument remains over what “The Brutalist” has to say about Zionism, but Reuben Baron’s review for Hey Alma posits that one truth indeed bridges the political polarity it leaves undefined:

“The message I think is clearest in ‘The Brutalist,’ whether read as pro- or anti-Zionist, is an explanation for why Zionism became so appealing to American Jews in the first place. America’s sins and Israel’s are forever intertwined.”

In the film’s final minutes, we learn of Tóth’s transcendent legacy. Juxtaposed with the boxy trophies of American megalomania, his work is remembered for its “immovable calm, informing occupants as they move through the world.” In doing so, his buildings inspire and uplift. They invoke the freedom he pursued before he built it himself.

The boldness of “The Brutalist” cannot be overstated. It’s a singular, once-in-a-generation spectacle enriched by stunning photography, a powerhouse score, and raw, engrossing performances. But weeks later, the wickedness it exposes haunts me far more than its hopeful conclusion. Nevertheless, I’m floored by what I saw and I will be returning to a cinema to see it again in 70mm very soon.

Sit as close to the screen as you can stand and don’t look away.